Svetlana Alexievich. The Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future (Voices From Chernobyl)

Proposal

Published by

- Suhrkamp Verlag, Germany

- Vremya, Russia

- Saeib Books, South Korea

- Lattés, France

- Citic, China

- Penguin Random House, UK

- Czarne, Poland

- Penguin Random House, Spain

- Ersatz, Sweden

- Iwanami Shoten, Japan

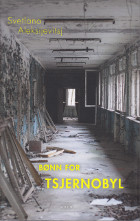

- Kagge Forlag, Norway

- 20|20 Editora, Portugal

- Owl Publishing House, Taiwan

- Edizioni e/o, Italia

- Artanuji Publishers, Georgia

- Edicije Bozicevic, Croatia

- Tammi Publishers, Finland

- Europa Publishers, Hungary

- Alma littera, Lithuania

- Megha Books, India (Malayalam)

- Ethir Veliyedu, India (Tamil)

- Folio, Ukraine

- Absynt, Slovakia

- Rayo Verde Editorial, Spain (Catalan)

- Fan Noli, Albania (rights have been reverted)

- Companhia das Letras, Brazil

- De Bezige Bij, The Netherlands

- Buzuku, Kosovo (rights have been reverted)

- Epsilon Yayincilik Ltd., Turkey

- Patakis Publishers, Greece

- Women Publishing House, Vietnam

- Pistorius & Olsanska, Czech Republic

- Olebella Publishers, India (Kannada)

- Kostova Antolog, North Macedoni

- Bolor Sudar, Mongolia

- Dalkey Archive Press, USA

- Paradox, Bulgaria

- Vinnochokh Publications, Bangladesh

- Madhushree Publication, India (Marathi)

- Grup Media Litera, Romania

- Angústúra, Iceland

- Koolehposhti, Iran

- Sprotin, Faroe Islands

- Hakibbutz Hameuchad – Sifriat Poalim, Israel

- Palomar, Denmark

- Jumava, Latvia

- Laguna, Serbia

The HBO TV series „Chernobyl“ is based among others on some stories from „The Chernobyl Prayer“.

The film adaptation „Voices from Chernobyl“ („La supplication“), 2015, by Pol Cruchten has been honoured as „Best Documentary“ at the Minneapolis St. Paul Film Festival and has been awarded the „Grand Prix“ at the Festival International du Film d’Environnement, Paris, and the Grand Prize „Cora Coralina“ at the 18th International Environmental Film and Video Festival (FICA) in Brazil.

The solos and chorus sung by those directly affected by Chernobyl give a chilling immediacy to the full scope of the Chernobyl disaster. There is the voice of the fire fighter’s wife who was kept from going to her husband because he was a dangerous “radioactive” object. There is the uncomprehending voice of an old woman farmer unable to see why she has to leave her village: “Why go away? It’s good to be here. Everything grows, everything flourishes.” There is a chorus of voices representing the “clean-up crew” soldiers for whom it has taken years to understand why girls do not want to make love to them. The beginning and the end of the book are each marked by the monologue of a “lonely human voice.” They are the voices of two women, who tended their husbands to the very end of a gruesome death from radiation sickness, watching their bodies literally falling apart. Alexievich emphasizes—and rightly so—that this is not a book about Chernobyl, but about the after effects of Chernobyl, about people living in a new reality that already exists, but which has not yet been comprehended. Those who experienced Chernobyl are the survivors of an atomic World War III. In this hostile world, “everything seems to be entirely normal, evil hides behind a new mask, one cannot see it, hear it, touch it, or smell it. Anything can kill you – water, the soil, an apple, rain. Our dictionary is out of date. There are as yet no words, no feelings to describe it.”

***

Excerpt from the Nobel Lecture 2015:

I resisted writing about Chernobyl for a long time. I didn’t know how to write about it, what instrument to use, how to approach the subject. The world had almost never heard anything about my little country, tucked away in a corner of Europe, but now its name was on everyone’s tongue. We, Belarussians, had become the people of Chernobyl. The first to encounter the unknown. It was clear now: besides communist, ethnic, and new religious challenges, there are more global, savage challenges in store for us, though for the moment they are invisible. Something opened a little bit after Chernobyl…

I remember an old taxi driver swearing in despair when a pigeon hit the windshield: “Every day, two or three birds smash into the car. But the newspapers say the situation is under control.”

The leaves in city parks were raked up, taken out of town, and buried. The ground was cut out of contaminated areas and buried, too—earth was buried in the earth. Firewood was buried, and grass. Everyone looked a little crazy. An old beekeeper told me: “I went out into the garden that morning, and something was missing, a familiar sound. There weren’t any bees. I couldn’t hear a single bee. Not a one! What? What’s going on? They didn’t fly out on the second day either, or on the third… Then we were told that there was an accident at the nuclear station—and it isn’t far away. But we didn’t know anything about it for a long time. The bees knew, but we didn’t.” All the information about Chernobyl in the newspapers was in military language: explosion, heroes, soldiers, evacuation… The KGB worked right at the station. They were looking for spies and saboteurs. Rumors circulated that the accident was planned by western intelligence services in order to undermine the socialist camp. Military equipment was on its way to Chernobyl, soldiers were coming. As usual, the system worked like it was war time, but in this new world, a soldier with a shiny new machine gun was a tragic figure. The only thing he could do was absorb large doses of radiation and die when he returned home.

Before my eyes pre-Chernobyl people turned into the people of Chernobyl.

You couldn’t see the radiation, or touch it, or smell it…. The world around was both familiar and unfamiliar. When I traveled to the zone, I was told right away: don’t pick the flowers, don’t sit on the grass, don’t drink water from a well…Death hid everywhere, but it now it was a different sort of death. Wearing a new mask. In an unfamiliar guise. Old people who had lived through the war were being evacuated again. They looked at the sky: “The sun is shining… There’s no smoke, no gas. No one’s shooting. How can this be war? But we have to become refugees.”

In the mornings everyone would grab the papers, greedy for news, and then put them down in disappointment. No spies had been found. No one wrote about enemies of the people. A world without spies and enemies of the people was also unfamiliar. This was the beginning of something new. Following on the heels of Afghanistan, Chernobyl made us free people.

For me the world parted: inside the zone I didn’t feel Belarussian, or Russian , or Ukrainian, but a representative of a biological species that could be destroyed. Two catastrophes coincided: in the social sphere, the socialist Atlantis was sinking; and on the cosmic—there was Chernobyl. The collapse of the empire upset everyone. People were worried about everyday life. How and with what to buy things? How to survive? What to believe in? What banners to follow this time? Or do we need to learn to live without any great idea? The latter was unfamiliar, too, since no one had ever lived that way. Hundreds of questions faced the “Red” man, but he was on his own. He had never been so alone as in those first days of freedom. I was surrounded by people in shock. I listened to them…